Why I Can’t Stop Consuming Apocalypse Fiction

Writer’s Note: Before talking about fictionalized apocalypse stories, it’s important to address up front another very real apocalypse that is happening in Syria and Turkey right now. As of this writing, there are over 36,000 people who have been killed from the disaster (and by time you read this that number has likely grown). Satellite images show that the scale of the destruction is similar to that of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake that leveled the city. I can’t help but think of Rebecca Solnit’s A Paradise Built in Hell that shows the incredible humanity that arises in the midst of disaster that is often more effectual, efficient, and humane than government efforts that tend to be slow (at best), inept, or harmful (at worst). Nonetheless, it is a disaster that requires us to pay attention.

As such, you can direct donations toward Syria and Turkey through some of the recommendations from this New York Times story and this NPR Goats and Soda blog post has some good tips on how to know where your money is going. Additionally, Team Rubicon is an excellent U.S. veteran-led organization that responds to disasters with search and rescue efforts and World Central Kitchen is helping to feed people displaced by the disaster. I should note that in looking for resources that would go directly to Syria, which is as impacted as Turkey, but experiencing a drawn out civil war, I noticed how difficult it seems to get help to Syria. This Washington Post story goes into that if you are also troubled by this and want to know more.

And with that, onto today’s story which is very much about thinking about the apocalypse…

I’m currently obsessed with apocalyptic fiction. This might seem an obvious observation given the subject of this project. But it’s been a slow-growing preoccupation as I’ve moved more deeply into various types of science fiction (a genre of which I’ve extolled the virtues of in a previous issue). I’ve been trying to wrap my head around what I find so enthralling about these end-of-the-world scenarios and also why I’m not completely horrified by them.

I dipped my toes in with Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower which didn’t exactly make me want to read more apocalypse stories right away. It’s a brilliant book because Butler was a genius. But it’s a tense read. Set in 2025 in a world that is on the brink of climate collapse and is amidst the associated breakdown of humanity as capitalism falls along with the climate, it felt just a little too close to home. A few months later, though, I read Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven about a virulent flu that kills 99% of people on the planet in a matter of weeks. The plot toggles between pre-pandemic and twenty years after “the collapse.” I was obsessed with both books and, while I read them, I’d attempt to talk about them with anyone who’d listent and they are also the reason why I started a Futurist Book Club.

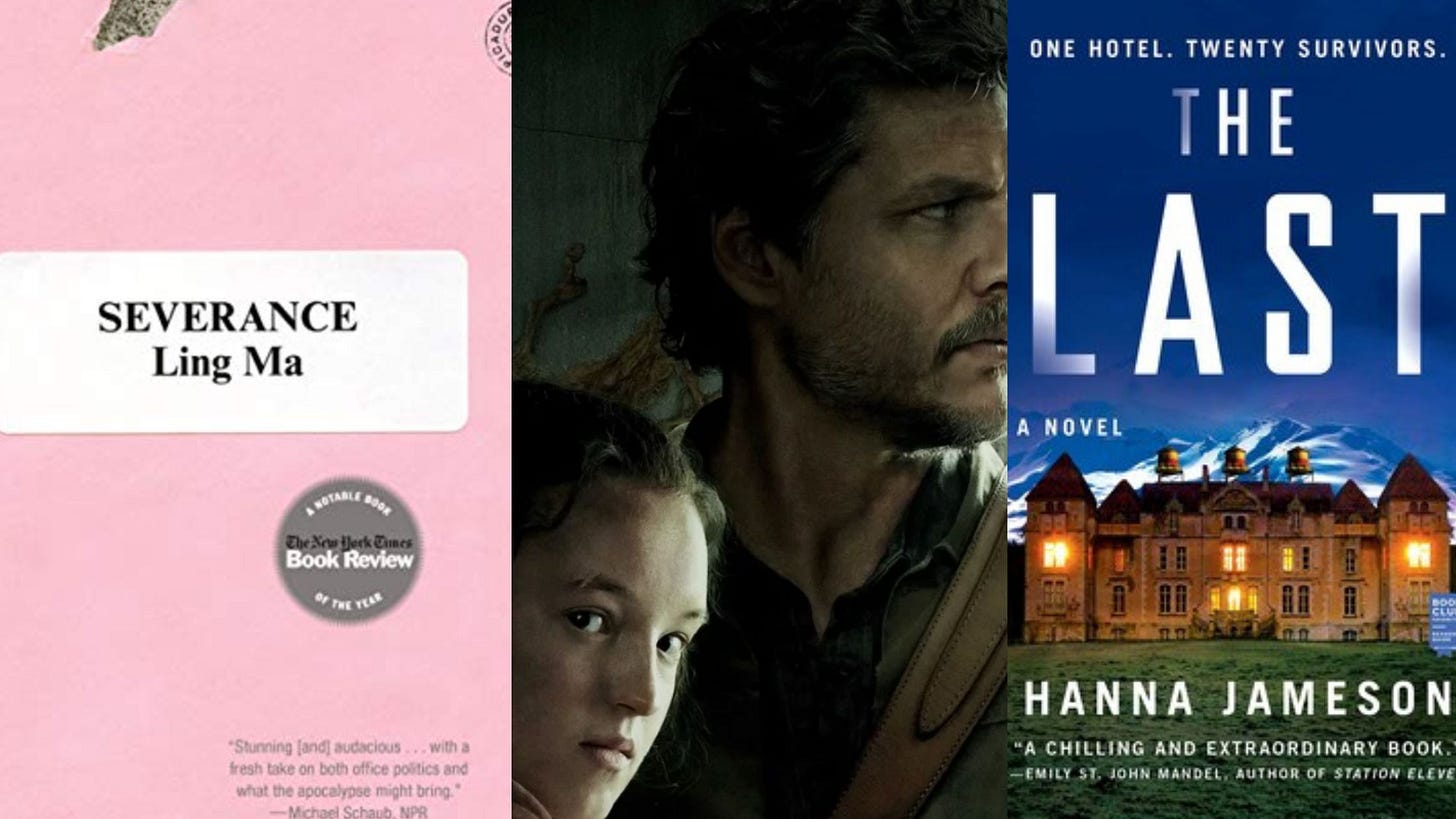

I took a break from apocalypse fiction for a few months, though. I needed a breather from immersing myself in post-collapse scenarios. And then my husband convinced me to watch HBO’s contribution to the cultural zeitgeist, The Last of Us. I have always avoided zombie apocalypse content which he loves, but when he said “it’s for book research,” I acquiesced as long as he wouldn’t complain about me distracting myself from the (many) scary bits by scrolling on my phone or doing something on my computer (such as writing Substack newsletters like this). Surprising myself, I was completely taken in.

I was captivated by the plot, the characters are complex and compelling (and I might also just have a major crush on Pedro Pascal), and the writing and storytelling is so well done. I’m also taken in by the plot lines of the first five episodes (at this writing what has been released) that involve the different ways humans have responded to constant terror. There’s beauty, there’s love, there’s ugliness, and there’s trauma.

My surprise affinity for the plot, the story, and the landscape flipped a switch for me. I wanted more apocalypse. I wanted more stories that could provide visuals of the post-apocalyptic landscape and scenarios where humans have adapted and what that looked like. And ones that didn’t involve zombies. And so I read Severance by Ling Ma which tells a story of another humanity-killing disease, but mostly tells the story of the main character, Candace’s experience as humanity was collapsing and in the few months after the collapse. The story is brilliant in that it’s a unique take on apocalypse fiction that explores a first-generation immigrant’s story and her relationship to the world pre- and post-collapse. It’s an even-toned tale where I grew increasingly frustrated by the characters in the story. And also it was a story that gave small glimpses of New York City succumbing to nature even in the first weeks of the collapse of humanity.

And now I’m reading another humanity-just-collapsed book cum murder mystery The Last by Hanna Jameson told from the perspective of an American man, Jon, who was attending a conference in rural Switzerland when nuclear bombs seemed to have hit most major cities in the U.S., Europe, and who knows where else. As he and the other guests still left at the hotel come to terms with the world ending and having to survive in an apocalypse, they find a young girl’s body in a water tank. Jon is on a mission to find out who killed her and why. But it’s not just the murder mystery that propels the story forward. It’s also about how everyone is reacting to the end of the world, how they connect or don’t connect with one another, and how they attempt to survive.

I’ve been back-to-back immersed in these stories over the last few weeks and I often stare up at the ceiling at night thinking about the plot lines as I’m trying to fall asleep (if anyone saw Sunday’s The Last of Us episode might get why that one really stuck with me). Strangely, this apocalyptic immersion doesn’t make me feel worse about our future. It doesn’t make me scared or even a greater sense of urgency to “prepare.” But I do find it fascinating, and in trying to probe that came across others saturating themselves into similar apocalyptic literature.

“Should one read apocalypse novels during apocalyptic times?” wrote Agnes Callard in this New York Times op-ed about her leaning on apocalypse literature in early Covid pandemic times. “Is there anything to be said for inflicting unnecessary emotional pain on oneself? I think there is.”

She goes on to posit that similarly to the times of feeling joy we want to deeply feel that joy and be in the moment. She believes many of us want the same for all of the other emotions. “If I have something to feel guilty about, I want to feel guilty,” she writes. “If something frightening is happening, I want to be afraid of it. Which is to say: When things are bad, I want to suffer and would choose to suffer and even seek out suffering. Why? Because sometimes the only alternative to suffering is a kind of alienation or numbness that is, as a matter of fact, worse than feeling bad — even if it feels better than feeling bad.”

I hear what she’s saying, but I admit, I was not at all attracted to apocalyptic fiction in those early pandemic days. I even had a hard time watching content of activities that I loved in pre-pandemic times–gathering, eating at restaurants, walking in city crowds–because it made me wonder if I’d ever have that again. That said, I’m in a different place now with the apocalypse. I think with climate change, it’s less dramatic and immediate as a pandemic and there’s mental preparation involved. Which maybe that’s what this current obsession is all about.

This article by Jeremy Anderberg in Book Riot about the appeal of apocalypse fiction posed some other options as to what is so compelling about an end of the world narrative. While all five of the article’s points ring true for me, these two stood out for the reflections that are coming up during the content I’m consuming now: “Apocalyptic scenarios offer us a chance to examine mankind” and “the apocalypse reveals who we truly are on the inside.” For the latter, I’ve been feeling disappointed in the characters’ response to disaster. Not necessarily the protagonists (although in part), but humanity’s response. Anderberg reflects on how we’re already so divided now, would an apocalypse really change us that much? Perhaps he’s right. But there’s some sadness about that, but also curiosity about whether these fictional depictions could be missing something. As Rebecca Solnit’s A Paradise Built in Hell showed that deep down inside most of us, we are prone to want to see humanity survive the worst and that brings out our innate altruism and community oriented-ness. I don’t see that in all of these apocalypse books, but there are hints.

Andenberg’s other point about revealing what’s inside ourselves is what really draws me to these apocalyptic narratives. “While we can examine mankind on a grand scale in our current world, it’s actually harder to examine ourselves on a smaller scale,” says Andenberg. “What kind of person are we when there aren’t bills to pay, job duties to attend to, rules of civility to follow? More than anything, a world in which survival reigns reveals our truest nature.”

Perhaps I want to live the disaster scenarios through an immersive story so that I can almost see myself in there. It’s a test in a way. What would I do in this scenario? How would I react in this scene? Who would I align myself with? It helps answer: “what would I do if the world ended?”

I also want to really think harder about how people might really react in a collapse. Would we be so prone to violence or would we be more collective? It has also made me think more about Andenberg’s other point about seeking apocalypse fiction to re-envision a completely different way of being. I’ve been wondering what apocalypse fiction I would write–in fact, this whole end-of-the-world obsession has got this nonfiction-writer-who-says-she’ll-never-write-fiction actually thinking about writing fiction.

This is all not to say that I don’t need a break from it. As seems obvious from the whole point of this project, I think about the apocalypse a lot. And it can be overwhelming. I realized as I stayed up thinking about The Last of Us on Sunday night that I might need a break. But these won’t be the last apocalypse stories I’ll consume (although I’m still not sure if I want to read Cormac McCarthy’s The Road). I’ll keep you posted here.

And of course, if you have your favorite apocalypse fiction, comment below and I’ll add that to my list.

End Note: I’m excited to introduce you all to another great climate change writer and Substack

by Dr. Parva Chhantyal. Parva and I connected recently because of the connectedness of our topics. I really love her approach to writing about climate change in very clear and science-based terms. I think you all would love her work, so I can’t recommend following her enough.Also stay tuned for a collaboration and we’ll be guest posting on each others’ Substacks. In the meantime, check out her work!

Thank you, Elizabeth. I got to try The Last of Us :).

My teenage years, and a decent part of my adult life has been enjoying the genre of apocalypse fiction. My absolute favorite was Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang by Kate Wilhelm. The one that got the most action from me is Alas, Babylon by Pat Frank. I was so angry at the actions of the main character and his utter inability to make the right decisions that it inspired me to put a question to all my friends, so that they might ponder BEFORE the disaster/atom bomb/whatever happened. In the story, the protagonist is given 24 hours notice that nuclear war is going to happen, and that his brother's wife and two children will be joining him. Whoa. Did he make some crazy useless panic buys! I got some awesome responses from my friends, which made up for the book!