Science Fiction as a Means to Reenvision the Future

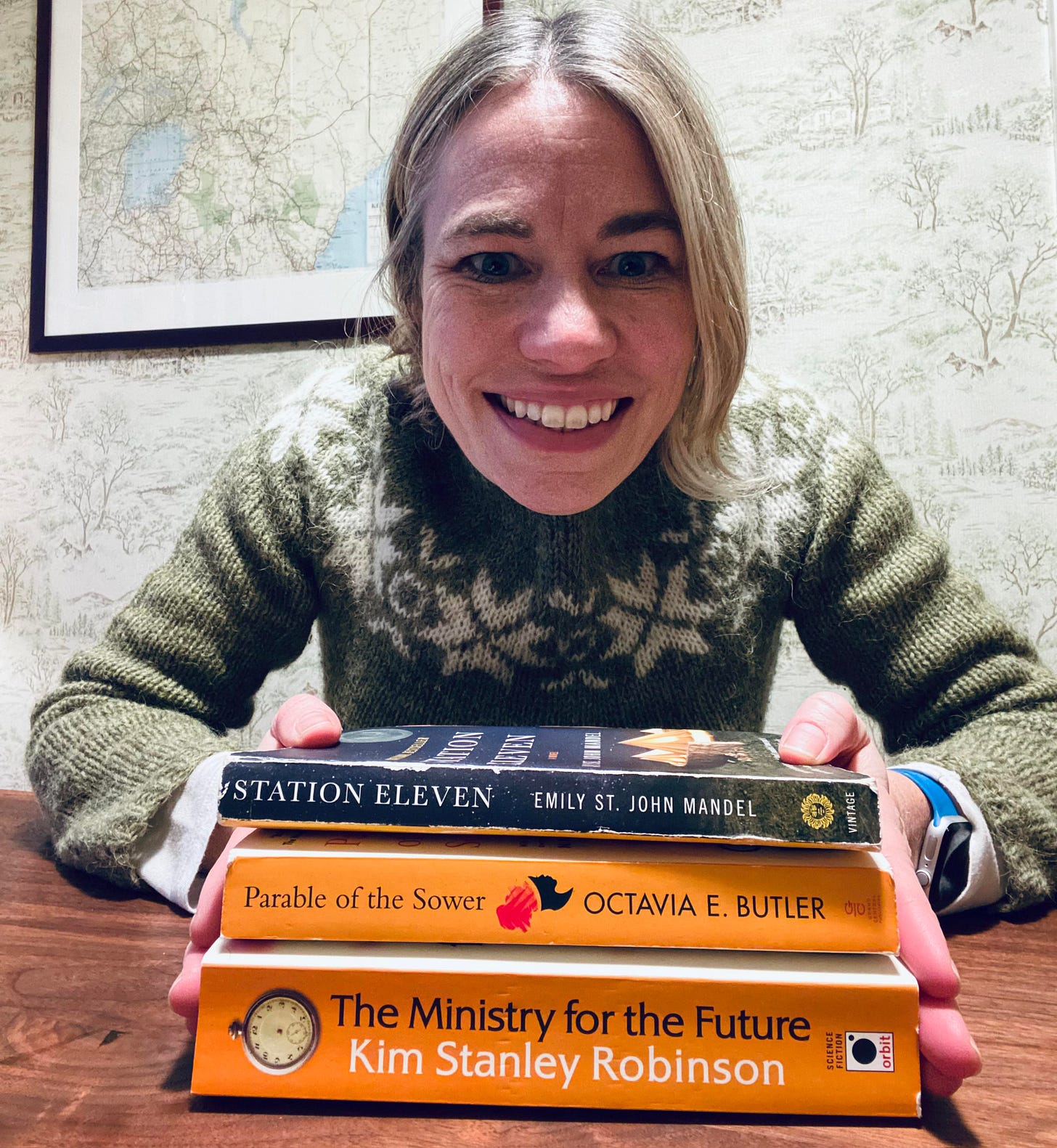

Plus some book recommendations

I believe that all organizing is science fiction - that we are shaping the future we long for and have not yet experienced.

-adrienne maree brown

Prior to last year, I rarely ever read science fiction. I wasn’t necessarily repelled by it, it just wasn’t my “thing.” Or so I thought. This journey to prepare for the worst has suddenly made me a science fiction convert, though. I erroneously thought that science fiction encompassed tales that were too far from the reality of my own world. I thought of aliens and spaceships and wars fought on galaxies far, far away. Those are fun for movies and comic books, but not necessarily for sitting down with a book. I wanted either true accounts from well-told narrative nonfiction books, travel stories that took me to places across the world, or absorbing page-turning novels that involved a world I could relate to, my world.

But I’ve recently realized that this assumption about science fiction cut me off from some of the most radical approaches to re-envisioning the world that we live in now. Science fiction is a way to investigate issues and stories in nuanced ways that just aren’t available to us when we’re dealing with the realities of the here and now (or even of the past). What I’ve come to learn about the potential for science fiction is captured in these words from writer, activist, and science fiction enthusiast, adrienne maree brown: “Science fiction is simply a way to practice the future together. I suspect that is what many of you are up to, practicing futures together, practicing justice together, and living into new stories. It is our right and responsibility to create a new world.”

How amazing is it that there is a genre where we can freaking create a new world. And what that opens up is the potential that we can do that in real life. While we can’t manifest magic and spaceships that jet off to far-off galaxies, and aliens, there are concepts held within these beautiful reimaginings of existence that we can create.

And so I’d like to share some of my science fiction conversion story with you through the books that have so captured why we should all be reading science fiction. This science fiction awakening began, as it has for many in the last couple years, with Octavia Butler.

Octavia Butler and “Parable of the Sower”

Octavia Butler is one of the most celebrated modern science fiction writers and, as Stephen Kearse put it in this The New York Times story, “committed her life to turning speculative fiction into a home for Black expression.” She earned all the top science fiction awards and a MacArthur “genius” grant, the first science fiction writer to do so. The MacArthur Foundation said of her work: “Her imaginative stories are transcendent fables, which have as much to do with the future as with the present and the past.”

This connection to the past and present that Butler manifests in her beautiful and page-turning stories is what struck me. She died in 2006, but her writing is as potent now as it ever was then. Perhaps even more so because of the prescience of her stories. This is especially palpable in “Parable of the Sower” which was my first foray into the world of science fiction and what single-handedly converted me to become a science fiction reader.

“Parable of the Sower” takes place in the not-so-distant future beginning in 2024 in Southern California in a world where society as we know it has crumbled thanks to global climate change and economic collapse (sound familiar?). There is some resemblance to the political structure that we know, but a political system (as it seems to be mentioned) seems to exist in symbolism only because every community and every person’s fate is in their own hands. The main character, Lauren Olamina, a 15 year-old Black girl whose father is a preacher and is growing up in a community that banded together to protect their once middle-class gated community’s walls from the dangers beyond–the street poor, the stray dogs, and the drug-addled pyromaniacs. Lauren, who suffers from hyperempathy making her debilitatingly sensitive to others’ emotions and pain, sees what many of her elders and even the younger people do not in the potential dangers and vulnerability to the world outside. Many around her exist in a denial believing all will go back to the way they once were. Lauren, beyond her years, knows otherwise. The book is her physical journey in this world and her emotional journey to create a new faith based on the potential of humanity.

And every person I’ve spoken with about the book has said this in some form or another: “it is just so close to home.” It is a hard read for that reason.The realities of a collapsed climate and unraveled economy that, as always, only protected the super rich, felt like a crystal ball showing us what our very-near-future holds. It’s a hard read. But it is a really good read and particularly in the burgeoning faith Lauren holds, which she calls Earthseed. In all honesty, the elements of Lauren’s faith didn’t stand out to me on my first read of the book. But as I’ve gone back to it and discussed this with the Futurist Book Club I coordinate, I’ve come to realize that that’s where the hope lies and those are the elements that show our own potential to reshape our existing reality here and now.

“Station Eleven” by Emily Mandel St. John

Taking place in a post-pandemic collapse, “Station Eleven” is not a book I would’ve picked up in the early part of the Covid-19 pandemic. But in Year 3 of the coronavirus pandemic, knowing that the world isn’t going to suddenly lose 99% of its population in a matter of weeks as it did in the “Station Eleven” world, I was fully absorbed in this surprisingly beautiful and optimistic look at a future that involved ideas around a future after capitalism and society as we know it is behind us.

The book follows Kirstin Raymonde who was eight years old when the world collapsed from a virulent strain of swine flu that killed the majority of the world’s population. The plot flips between the past revolving around an actor Arthur Leander (who died from a heart attack on stage performing as King Lear on the day that marks the beginning of the end of the world) and 20 years after “the collapse.”

It’s the after times, the 20 years post-collapse world that provided me with hope. It’s a story that doesn’t involve the kind of chaos and fear and ever-present danger that would happen in the immediate aftermath of a collapse. Rather it is a calm, somewhat peaceful look at what life looks like well into the age of post-collapse through the perspective of a traveling symphony. Not that there aren’t moments of fear and danger (there has to be some plot that drives the story forward), but it feels secondary to the glimpses of people who have learned to live in a reality that is completely different from what they knew. It also shows the bits of tension between the people who knew the pre-collapse times and those who were born after or who were too young to remember an age of cell phones and airplanes and capitalism.

My takeaway was that if and when there is a collapse, life can and will go on. And there can be beauty in that world such as the art created and shared by the traveling symphony.

“The Ministry for the Future” by Kim Stanley Robinson

“The best science-fiction nonfiction novel I’ve ever read”reads Jonathan Lethem’s quote from the cover of the book which explains a lot about why this book is so compelling. Taking place between now and the next 30-40 years, “The Ministry for the Future” poses one of the most optimistic views of what the world could accomplish to evade the most catastrophic effects of climate change if we work together from all sides to solve this problem.

This tale of climate fiction–a genre that specifically deals with the topic of climate change— revolves around a new UN Ministry for the Future led by Mary Murphy, the head of the ministry. While the story follows Mary and the works of the ministry throughout the decades, it also involves characters who provide ground-level perspectives of both the effects of climate change (e.g., a devastating heat wave in India) and the effects of progressive policies as the ministry’s work began to take hold (e.g., the powerful economic and environmental impacts of promoting regenerative agriculture for farmers in low-income countries).

Admittedly, I got about half-way through wondering “when is this supposed to get optimistic?” At first, it felt like an accounting of all the shit we’ve already done wrong and are doing wrong and how that’s going to impact the most vulnerable communities first. But in order for it to be believable, it had to include all of that. About half-way through there was a subtle turnaround and I finished the book feeling hopeful that it’s not too late.

“The Ministry for the Future” felt less of a work of science fiction and more like a guide on how to solve this problem as a global community. It’s an example of how science fiction/climate fiction can be an act of thinking creatively about what we can actually do about vividly creating a world that we can make happen.

These books show how science fiction can serve as a cautionary tale of what is to come if we don’t act now and it serves as a place of hope to envision what the future can be like. They show the radical potential of the genre to frame how we think about the world as we know it. And these three books, in particular, show the varied potential of science fiction as the perfect genre for those of us who want to create a better, more just, healthy, and environmentally stable world.

If these books intrigue you and you’re interested in discussing them with a group of awesome people also rethinking the future, message me or comment below and you can join the Futurist Book Club!