The Existential Dread of Creating a Family Emergency Plan

A Note: This post is about family emergency plans for a disaster that is notably not caused by climate change (an earthquake). However, it is relevant to climate change because as the world’s temps change, more frequent and devastating disasters are inevitable. We already have more intense hurricanes and massive flooding (as we speak in Puerto Rico and Pakistan), drought and heat waves and wildfires (as we speak all across the Western U.S.). The list goes on. So when we talk about preparing for a disaster, we’re also talking about preparing for the disasters that come along with climate change. And each one of those disasters is an apocalypse in their own right. Through that lens is how we can approach individual and community disaster preparedness at all levels.

While at a meeting in Portland’s Chinatown neighborhood last week, the table shook a little bit. It was not an earthquake. I knew it was not an earthquake. It was just someone moving around a bit and knocked the table. But that shaking did something to me and awoke anxiety that’s always lingering under the surface.

I was suddenly well aware that 1) I was on the third floor of an old, Portland building, likely an unreinforced masonry building, and 2) I was across the river from my child. Translation to those not so steeped in earthquake anxiety: I was in a building that was almost certain to collapse in spectacular fashion as the earth shakes violently and even if I’m able to get myself out of said building, almost every bridge in the city (except one) is likely to be down and I will be trapped across a body of water from my only child who is but five-years-old.

These kinds of anxieties have occupied my brain since we moved to Portland in 2016. In fact, they have occupied my brain since before we moved to Portland when, still living in Baltimore, we were trying to decide whether to move to my hometown of Spokane or to Portland where many of my college friends now live. Around that time in 2015, Kathryn Schulz published her New Yorker article entitled “The Really Big One” that detailed in very meticulous detail about the wide scale disaster that is eventually to befall the coastal parts of the Pacific Northwest when the Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake hits the region with its 9.0 magnitude shaking (this notably went into the “cons” category for Portland). For a region that is not prone to earthquakes, this came as a shock to many people who live here or are from here (except, of course, many scientists who have been trying to sound the alarm for quite a while now).

Schulz’s article and subsequent coverage did something to the psyche of the Pacific Northwest region and really helped to publicize the need for preparedness. While the talk of “the earthquake” is not as frequent as the couple of years after this article was published, a normalization has occurred around the acceptance that an earthquake will happen (anytime between now and a few decades from now) and a lot is happening to prepare the region’s infrastructure and community resiliency for this inevitability (albeit at the typical governmental bureaucracy pace).

That said, the normalization has also left some complacency. And if not complacency, a paralysis around how to actually prepare. I have conversations about “the earthquake” with many friends, but the majority of people I know don’t have food or water stored and don’t have a family emergency plan. Confession: I also do not have a family emergency plan.

Now, here’s the thing, how much food you have stored and the plans you lay for an emergency are actually minor to survival. I have even written about this in this CityLab story from a few years ago where I wrote the following:

While having a store of food and water to withstand days or weeks of service outages is important, research shows that a supply of helpful neighbors might be your most critical emergency preparation. “The number-one thing I always say to community groups, ‘Do you want to survive in a disaster? Well, then you better know your neighbor,’” says Lori Peek, director of the Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado Boulder. “In the immediate life-saving moment of the disaster unfolding, that’s when our communal ties are exceptionally important. If you’re isolated, no one will know to come rescue you.”

I still believe in that wholeheartedly and so do all of the disaster researchers out there I interviewed. And it’s pretty much what this whole apocalypse-prepping book is leading us to: building community with each.

However, there is a powerful emotional and existential release that can come from actually creating a family emergency plan.

So, in the “wake” of that moment at that slightly shaking conference table and the inordinate amount of anxiety that welled up in me from it, I decided this is the moment we need to create our family emergency plan. Don’t ask me why it took me over six years of living here, seven years since I heard about the earthquake, countless anxiety-ridden moments stopped in traffic on one of the many Portland bridges, and the months of research I did for an article about emergency planning. But here I am. Doing this for me and my family. And also doing this for you. And, maybe a little, doing it because the preppers I follow on Instagram have followed through on their commitment to provide resources around personal resiliency and reminded me that it is, indeed, National Preparedness Month, and we all should be doing this. So here we go.

About Our Emergency Plan

First of all, there are countless resources out there about creating a family emergency plan. I found, though, that in my needs-to-think-through-every-scenario mind, they all felt just a tad simplistic. But honestly, they could very well work for you.

This one from the Marines of all places (downloads for emergency plans are found on the right-hand side bar of the page) was actually the most helpful in guiding some of the questions I ask myself. Yet still not as detailed as I would have liked.

So here are the questions that guided my planning process.

What disaster is most likely to affect us/easiest to strategize around?

Because the earthquake is the easiest and most obvious form of disaster in my mind, and honestly the one that I can concoct the most elaborate scenarios through, that’s the one I’m going to use. Interestingly, though, this is probably the least likely disaster to befall us given the region’s propensity for wildfire and most recently deadly heat waves (all thanks to climate change).

However, my home is not in or near the wildland-urban interface (basically where forest meets residential neighborhoods). That isn’t to say we aren’t vulnerable to fires, because we are. House fires are the most likely emergency that could befall us. And we need to consider this, too.

That all being said, the earthquake is still the easier one for me to process through my mind and it’s a place to start. I can create the other scenarios once we have a clearly established plan for the earthquake.

What are the various scenarios given our everyday habits/work environments as well as special circumstances?

We should all be so lucky if an earthquake hits us in the middle of the night when everyone is home from work and school and we are surrounded by our neighbors. Because honestly, that is the best case scenario, even in Schulz’s accounting.

The challenges are when we’re scattered all over the city. I went through several scenarios. I work from home which is within walking distance from my son’s school. So the likelihood of me being close by during a disaster is high. However my husband works at a hospital across the river on a hill and, if he doesn’t have to stay and help and aid the injured (that’s something we need to find out), he will have to figure out a way to 1) communicate with us and, eventually 2) get back across the river. And, of course, occasionally, I find myself in meetings or on errands in other parts of the town including across the river in unreinforced masonry buildings.

The really difficult scenarios for me to consider and process are in the “special circumstance” category that involves the question of “what if this disaster occurs while me or Cory is out of town?” But it’s a question that must be considered.

What are the steps to take in the immediate aftermath of the emergency?

Questions to ask: Where do you evacuate to? Who is your first point of contact? Who is your out-of-town contact that can relay messages if phone lines are down? How and when do you figure out how to reunite? Who else do you need to check on?

Who are the people in my emergency network?

Enter the community part of this process. Who are the people that are your emergency community? Who is your disaster pod, so to speak? Given that we’re in year three of a pandemic, we all know what we mean by “pod.” This is a group of people who become your touch points and with whom you have a joint plan. They are also the people who can account for you or note your absence and do what they can to find you in the immediate aftermath.

At this moment of planning, this requires reaching out to those people in your disaster pod. Ask them if they want to “pod up” and if there’s anyone else who should be there. Naturally, my sister and her family who live less than a mile from us are in our pod. The others are our immediate neighbors with whom we already have regular preparedness conversations with. These should be people within walking distance.

What we need to do (and haven’t done yet) is to convene ourselves as a pod to discuss our individual family emergency plans, to share notes, and adjust as necessary. This may or may not include some beverages and laughing and perhaps a game night to make it more fun and not just about envisioning a spectacularly awful disaster.

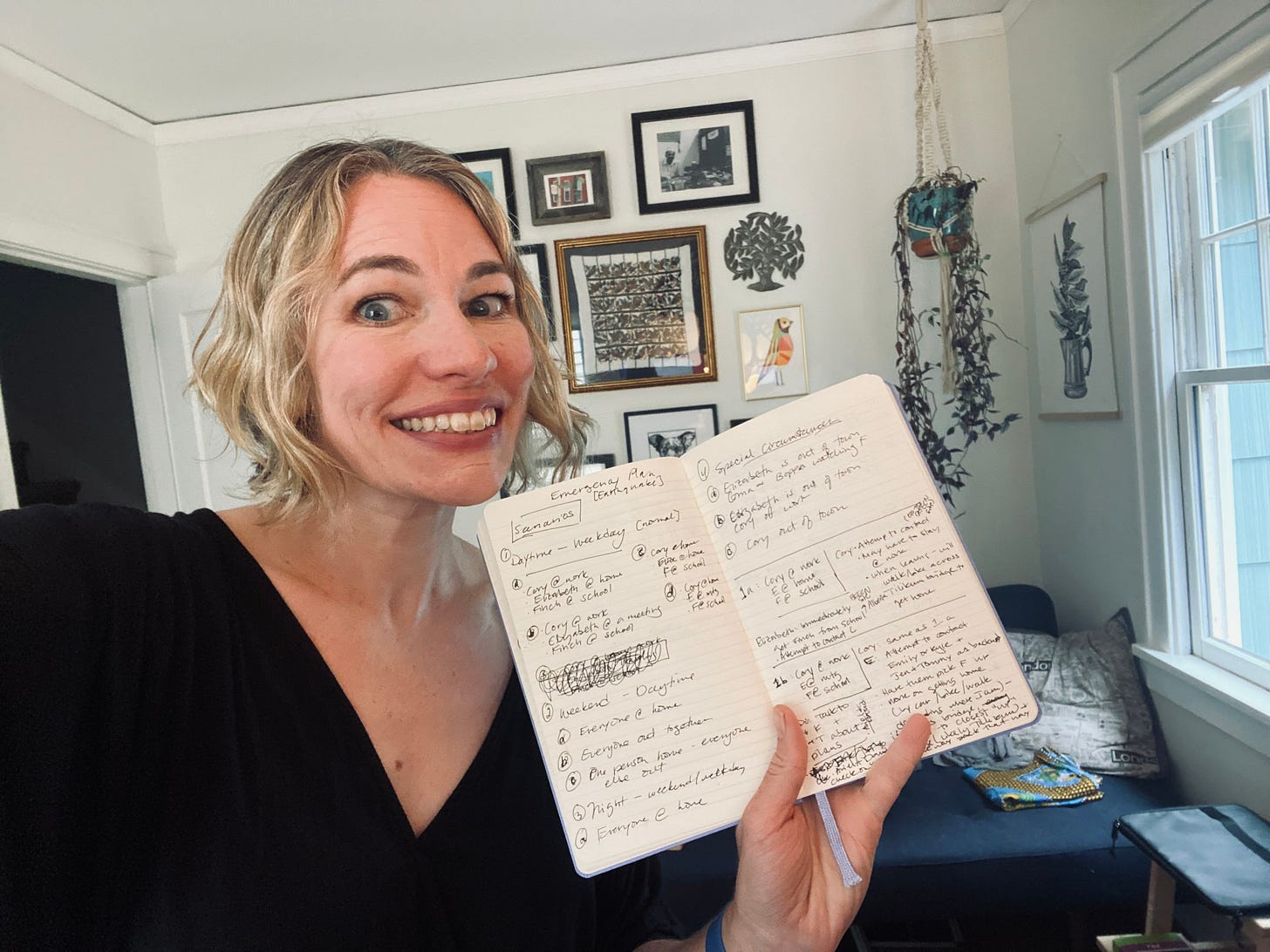

Where my emergency plans are at now

I’ll say this: we have not done all of this. I have more or less done a bit of each of these things, but we do not have a concrete plan as of yet that will then be distributed to all people in our disaster pod. But I’ve started the process, specifically the scenario piece and casual texts sent to my sister and neighbors as such “want to be in our disaster pod?”

And y’all, it’s a heavy process. With every scenario I envision, my brain flash forwards and creates a small, 4D movie where I see what is happening and feel a small sense of the fear and terror that I might in that moment. It’s hard. But also the more I got into it, the more I was able to compartmentalize.

I was talking to a friend about this process the other day (we have confided in each other that we share the same anxieties and think about the scenarios often) and she had something along the lines of this to say: “All we need to do is just create the plan and then put it away.”

What she’s saying is that once we’ve created the plan, we can take comfort that we did the work that we needed and we can reach for that in crisis, but we don’t need to keep thinking about it. The thinking is done.

She is right. The creation of this emergency plan is an emotional process for people like me (maybe not for everyone, some are better at compartmentalizing than others–like my dear spouse who, thanks to his medical training, is quite capable of compartmentalizing the potentialities). But having done it, you can rest easy that even if the disaster might not unfold in the exact way you planned for, as it inevitably will, you have put the pieces in place that sets you up for strong problem solving in the moment.

Now, questions for you dear readers

Have you put your family emergency plan in place? What did it entail? What do you still need to do? What did you learn from the process? And, do you have any helpful resources you can share with others?

I want to hear how others are preparing, or not preparing, or what is keeping you from doing it.

In the meantime, happy prepping!

Also, one more resource. This Prepare! Guide from the American Red Cross of the Cascades Region is also a useful resource for preparing in general. It is somewhat helpful for the family emergency plan, but what I find most helpful is the calendar that pieces out the preparing by “week” versus giving you a huge long list and say: “okay now go do all of this now.” It bite-sizes the preparing. You may also find it helpful.

I think "preparedness" has been really well marketed and I've bought into it. It's a taboo set of products - sort of like weight loss and sexual wellness that don't get talked about much, but which are omnipresent none the less. It is easy to go on a binge at Amazon and Sportsman's Warehouse and feel prepared in the same way it's easy to buy a rowing machine and assume fitness will just happen as a result.