Resisting Busy-ness

A brief moment outside of the cycle of productivity

When, 20+ years ago, I was preparing for my two-year stint as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Malawi in Southeastern Africa, one of the major questions on my mind was this: what would I do with ALLLLL the spare time I would have?

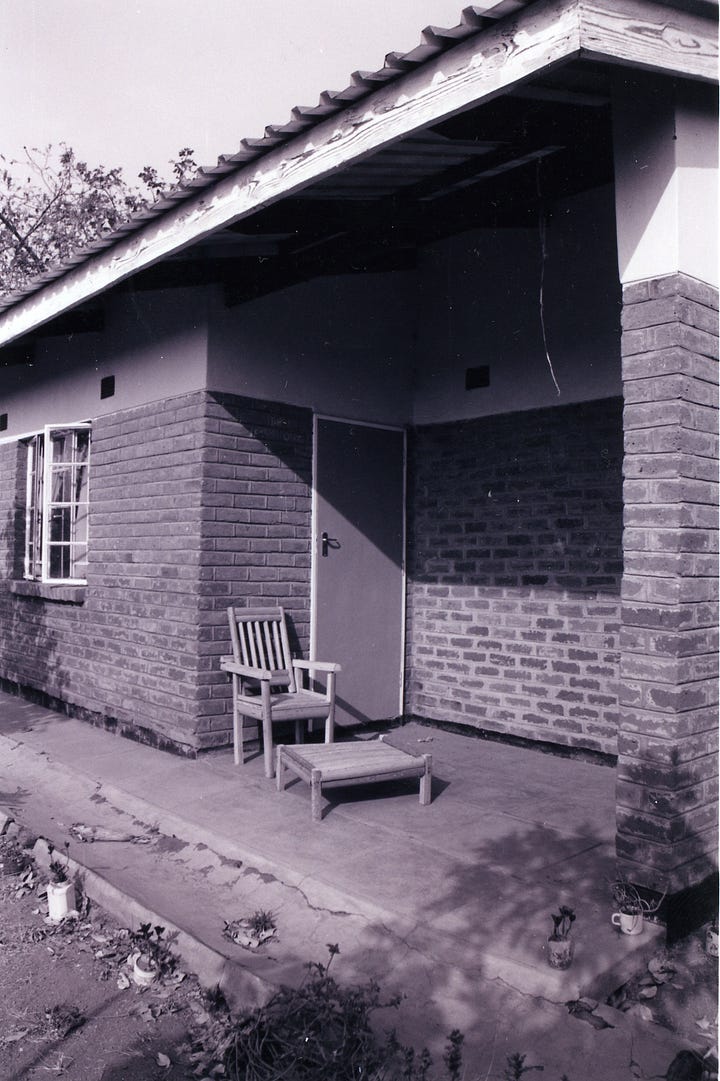

Malawi was on the list of “least-developed countries” in the world. It still is two decades later—maybe sometime I’ll investigate this definition of “least-developed” because there’s something quite problematic about it, but that’s for another post. But in the logistical and practical sense, that meant that I was heading off to a community with no electricity, no phone service, no internet, and a house with no running water. I would not have the kind of electronic diversions such as television or internet or anything having to do with a phone. And my social life was bound to be different in rural Malawi.

I was the kind of person who was constantly going, always had plans, and just generally lived a fast-paced life like most Americans. If I was sitting doing “nothing,” there was always a nagging feeling in the back of my mind that I should be doing something “productive.” Read: very American.

As I packed and wondered what I’d do for “fun” in my community, I brought books on gardening and seeds with the idea that I’d become a gardener and when I arrived in-country, I bought a travel guitar and some music books off a departing volunteer thinking I’d finally teach myself how to play the guitar. But what else? Wouldn’t I be bored?

The answer is yes, I was bored. A lot. And honestly that was one of the things I came to treasure. It was one of the things I wanted to hold onto when I returned home after two years.

I’m a classic extrovert and need to be around people, so it really was a worry for me before I left. It turns out I never really got away from people. I was around people quite a lot in my community. I didn’t have a set schedule like teachers, I basically had to make my work. But when work was slow and I felt the need to be around people, I could just walk over to the health assistant’s office at the health center I worked at and there’d always be a few outreach workers shooting the shit. I’d travel out to villages with my colleagues on their immunization rounds (at least in the beginning when I was still trying to find my place). And later on, my friend who was also a colleague and I decided to “start a women’s group” which ended up being more of an excuse for us to hang out with each other most of the day once a week.

But when you’re in a community with people from a vastly different culture than you are, socializing is even more exhausting. So I found myself often craving alone time, even craving boredom.

I would travel into the capitol city, Lilongwe, every month or so to check and send emails, take hot showers at our Peace Corps house, go out on the town with my buddies, and watch the occasional movie. But also to socialize with my fellow Peace Corps Volunteers with whom I could commiserate about our shared experiences.

But even those weekend getaways were exhausting when I had come into a habit of slow living. I was eager to be back in my space, cook my own food, and just read.

I was thinking about this recently and reminiscing how much I loved my little space at home and how much I actually looked forward to boredom. And I also thought about how much the Malawians I worked with and became friends with enjoyed their lives. Certainly they lived in a country on that list I mentioned above, and of course they deserved more than the centuries of colonialism and imperialism and now international development created for them. But my Malawian friends found joy in the small things. They didn’t need the diversions we’ve come to think we rely on. I learned a lot from the slower-paced life. I kind of got used to Malawian time (which is to say that anything slated to start at a certain time would actually start at least an hour later than that, but probably definitely more). I never really could get being on time out of my system, but I did learn to bring a book so that I had something to do.

I found myself here in America, twenty years later and modern American living has become an even more ripe with distractions. Boredom is harder to come by and we’re raising generations that we almost have to train to be bored. It’s even tougher when the generation raising them can’t put their phones down for five minutes (talking about myself here). There is no end to the grind, there’s no detachment from the idea of “productivity.” You will never win. And all for what?

This was the thought that came to me as I momentarily came out of that loop during my son’s winter break. I fully took the two weeks off. OOO message in place and very rare glances at email, I pretty much went offline. The first week was a blur of Christmas stuff (fun but oh so freaking exhausting), but the second week was slooooow. In a good way.

Usually, the break time after the Christmas holidays can be a nightmare with a busy kid in the house and all of us having some sort of cabin fever especially when it rained pretty much constantly the entire week. But there were glorious days where I realized there were extended moments that I just looked up at the ceiling for several minutes without thinking about anything in particular. Or I zoned out while I had music playing in our living room and I just felt what I was hearing.

When I realized what happened, I noticed a kind of zen had taken over my body. Tension was gone from my shoulders and I had kind of let go of doing anything “productive.” While I still haven’t found a way to fully untether myself from my phone, I found myself reaching for it way less.

I can’t say that the idea of productivity or the worry about not doing something productive will ever leave my mind. I did have many moments where I internally chastised myself for not writing when I had free time. I didn’t meet any of my writing goals made at my accountability group meetings during this whole period of time and it did nag at me. But then, I swatted that nagging away because who does it harm that I didn’t sit down and write an essay about my kid loving rocks only two of the five days I said I’d write? No one. I’m not even harmed by that. It’s that productivity brain that gets at me.

I’ll also say this, I’ve never truly been able to do nothing completely. Over the two years in Peace Corps I read over 100 books. And during this two weeks off, I was almost constantly reading or cooking or listening to music or a podcast. I had a few moments of staring into space, but wasn’t really doing “nothing” per se. But that’s not the point. The point is that I wasn’t doing something for the sake of productivity. I was doing something enjoyable to me and not in the service of capitalism. But in Peace Corps I was not as productive in the ways I intended to be before I left. For example, I did not learn the guitar or become any semblance of a gardener. I picked up the guitar maybe once and I tried to garden to spectacular failure—which you can read all about here. And during winter break, I didn’t really do anything that was tied to traditional productivity.

That’s the kind of “doing nothing” Jenny Odell advocates for in her amazing book How to Do Nothing. And she argues that it’s nothing short of a radical act.

“I hope that the figure of ‘doing nothing’ in opposition to a productivity-obsessed environment can help restore individuals who can then help restore communities, human and beyond,” she writes.

To that I say, hell yes. But also I say, I hope I can carry this through to the everyday when I’m back to the grind. For the moment, I’m holding onto the joy of the quiet moments of a winter break of doing nothing.

A couple years back, I turned my phone on silent and turned off notifications for most of the apps. Now it stays on silent unless I'm expecting a call. I check my email and social media whenever I think of it. It's been an amazing break from all the constant nonsense and noise.

It's not quite as immersive as your experience, but I did something similar in the mid aughts. I had recently separated from the Navy and decided to take a survival class in Northern AZ, which was a couple of months long. Off-grid, far enough from Flagstaff to not get cell reception (at the time), water had to be trucked in.

It took a few days, but once I adjusted, I really started to enjoy the pace of that that existence. No alarm clocks, no emails, no set schedule besides when the instructor was ready to teach. We learned friction fires and shelter building, tanned our own deer hides, and made tools from obsidian that was natural to the area.

During the frantic nature of our capitalist lifestyle of overconsumption, I really miss that time.