What is "The Apocalypse" to Indigenous Peoples

Some reflections related to Indigenous Peoples Day

This is a picture of one of my favorite places in the world, The Columbia River Gorge. It’s a photo taken from a viewpoint from a hike called Angel’s Rest looking West as the Columbia River moves toward the Pacific Ocean. I love this particular part of the world not only because I can get to amazing hikes in the Gorge within 30 minutes of my house, but for the vast expanse of it. There’s something about this place that makes you realize just how small you are in the world.

One thing I’ve come to realize over the past few years, though, is that if you look close enough and learn enough of the history, there are signs of an apocalypse here. This, like many places in what is now North America, shows evidence of an incredible apocalypse that didn’t take place that long ago—and in many ways is still very much taking place.

The apocalypse of which I speak began with European colonizers arriving in this land, claiming it as theirs despite full societies of people already living and stewarding this land for many centuries. They did this in the name of “Manifest Destiny”—a thinly veiled religious justification for seeking the greatest amount of power by any means necessary. Over centuries, the U.S. government systematically perpetuated genocide by creating policies for displacing and killing Indigenous peoples and, for those they didn’t kill, seeking to kill their culture and beliefs.

This is a history that so many of us—including me—did not learn growing up. Many of us are still unlearning the whitewashed history we were taught and relearning the history of our landscapes from an Indigenous perspective. One has to seek those out.

I began this unlearning/relearning journey a couple of years ago when I read Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. It was, well, mind-blowing for me. I knew the history, in theory, but absolutely didn’t know the extent of the reign of terror the United States maintained over Indigenous Peoples on the land that I currently call home. It began a journey of both acknowledging the Indigenous peoples on whose land I live, play, and work, and, more importantly, learning more about the peoples and history of these places. It started a journey that opened my eyes to what I was not seeing before.

So now, when I look closer at this beautiful Columbia River Gorge landscape, I see what we often call evidence of modernization as, rather, evidence of an apocalypse. The dams along the Columbia River caused irreparable harm to the ecosystems and wildlife in the area as well as to the traditional livelihoods of the Indigenous peoples’ of the region.

Celilo Falls

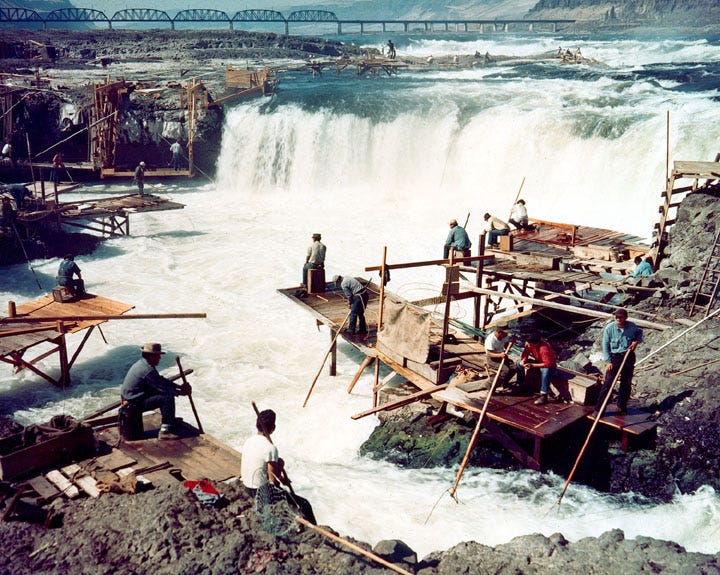

I learned more about one such place last summer when a friend and I were in Washington’s Yakima wine-country trip for my 40th Birthday. We decided to visit The Yakama Nation Museum & Cultural Center in Toppenish, WA (I admit that not the average wine-country visitor goes there, but honestly, they should!). While there was a great deal about the tribe’s traditions and culture, there was an expansive section about Celilo Falls on the Columbia River which was an important tribal fishing area for the Yakama people. The exhibit felt less of a history and more of a memorial (and, in a sense, a call to action) for an important site for tribal people because when the Dalles Dam was finished in 1957, the Celilo Falls site was completely flooded.

You pass the site now—just a few miles East of what is now The Dalles—and there is no sign of the craggy rocks on which sat the platforms where tribal fishermen used dipnets to catch salmon swimming upstream to their spawning grounds each year. It is now just a flat expanse of river. There is a public park along the river now and there is an unincorporated village around there, but very few people still live there as the majority of the adjacent settlements were inundated after the dam was built.

To learn more about Celilo Falls from an Indigenous perspective, I highly recommend this video by Confluence, an organization that seeks to tell the stories of the Columbia River from an Indigenous perspective.

The Petroglyphs on Horsethief Lake

Another site, just off Highway 14 on the Washington side of the river,r there is an outdoor museum, of sorts, that tells another story about the apocalypse. They are historic petroglyphs that were originally on Columbia River rimrock serving as guideposts for Indigenous travelers in the region. They were moved before their original placements were flooded by The Dalles Dam.

I wrote a blog post mentioning these petroglyphs last year:

“The story of these petroglyphs shows two elements of the story of that place: the history of the Indigenous people and the destructive effects of settler colonialism. What would the river look like, what would the salmon run be, what would the state of the environment be if we hadn’t dammed up the place?”

As such, these petroglyphs are evidence pulled from the wreckage of an apocalypse.

What We Learn from an Apocalypse

These examples are but a couple of many pieces of evidence. The loss of the salmon run, the changing and shifting ecosystems, the displacement of Indigenous communities, etc. Those are all evidence of an apocalypse that we have created.

So what can we learn?

One major element is there are survivors of this apocalypse that are with us today. Watch The Confluence Project’s stories from the river video and you see these survivors. While many Indigenous people do still live with the trauma of that apocalypse, there is a resiliency they possess that we can learn from. And there’s essential knowledge about ways of being that are much more rooted in knowing the land, the waters, and the natural spaces that are around us and caring for them as deeply as if you would care for any beloved family member.

I don’t claim to have any true grasp of the knowledge of survival, but I think a lot about the term “survivance” that has taken hold through Gerald Vizenor, a White Earth Anishinaabe writer and scholar which is essentially the combination of “thriving” and “survival” and seeing it as an act of resistance. It is a term that I think those of us looking for answers to how to create a better future can reflect on.

To reflect further on this, I offer The Decolonial Dictionary’s assessment of the term:

“‘Survivance’, in this sense, names the conjunction between resistance and survival – calling attention to the fact that not only have Indigenous peoples survived the genocidal ambitions of settler colonialism, but have continued to enliven their cultures in fluid, critical and generative ways. The term thus resists the static overtones of ‘survival’ and instead emphasises the ways in which Indigenous peoples have created counter-poses/positions to those that are marked out for them by the settler-state through stereotypes, popular culture and national mythology.”

For anyone who cares about the future of this Earth and the beings on it, isn’t that something beautiful that we can learn from and get behind? I leave you with this question: How can we engage in this act of survivance and what does that look like when we think of climate justice?

A Note: A big component not mentioned above is The Land Back movement which is a movement with a goal to return Indigenous land back to the original stewards (which is, to say, all of the land in North America…as well as South America, New Zealand, Australia, etc. etc.). Check out The NDN Collective for more on this movement. But also I urge you to learn about the Indigenous resistance movements around the world, the country, but especially close to you. What are tribes and/or Indigenous organizations doing and how can you be an ally/co-conspirator in their work? And at the very least, know whose land you’re on—https://native-land.ca/ can be used as your starting point (there’s a mobile app as well!).