Hi Everyone! I hope your holiday was cozy and, perhaps, reflective and didn’t include too much media.

I was on

podcast which was published yesterday to discuss climate grief and the cognitive dissonance we’re experiencing in the face of disaster and the climate disasters that are creeping ever closer. It was truly a joy to talk with my amazing writer-mom buddies and Miranda Rake. You can listen to it on Substack here as well as on Spotify and Apple podcasts.And with that, I’m back to writing about fire.

Ever since we moved back to the Pacific Northwest in 2016, I’ve developed a kind of obsession with fire. This was a surprise to me because when we moved, all I could think about (and still something that dominates my mind) is the imminence of the Cascadia Subduction Zone Earthquake thanks to Kathryn Schulz’s 2015 New Yorker story that laid out the potential destruction in vivid detail.

But then in September 2017, the Eagle Creek Fire in the Columbia River Gorge woke me up to the fact that perhaps fire was the more imminent threat. Started by a teenager with fireworks over Labor Day, it quickly grew engulfing the Columbia River Gorge scenic area, even jumping the river at one point into Washington State, and overall burning nearly 49,000 acres. While some of the communities were evacuated, only four homes were burned in the fire.

It was the first time I had experienced the pall of apocalyptic smoke. We were also less than a month out from my son’s cleft lip surgery which can throw and already bad-sleeping five month old back into the newborn levels of wake-ups and I was in a dizzying sleepless haze made even more surreal by a layer of smoke that, up until that point, was the worst I had ever experienced.

I vividly remember coming out of the grocery store, looking up at the bright orange-red sun (which one can look at directly when a thick layer of smoke is above you), and teared up with a strong sense of foreboding. That foreboding was not unwarranted.

What would follow would be even more devastating fires such as those in 2020 where millions of acres burned, thousands of Oregonians were displaced, and the rest of us were forced inside for a week thanks to 500+ AQI air. Eagle Creek was small beans compared to the level of destruction and displacement of the Fall 2020 fires.

But since the 2017 Eagle Creek fire, I’ve become fascinated with fire. Scared, yes. But also in awe of it. There had always been fire in my life, but nothing like this. I grew up in the Pacific Northwest, Spokane, WA to be specific, a much dryer climate than ours currently in Portland. I remember only one large conflagration growing up that was dubbed Firestorm ‘91. In fact, although I was only 10 years old, I distinctly remember the dry, windy air that preceded the fire. It was an eerie feeling. It ended up burning around 50 acres near the Spokane airport and the event loomed over us for years growing up there. But what was called a “firestorm” then seemed to be nothing compared to what we experience today. Just last summer, a fire in almost the exact same area of Firestorm ‘91 burned over 300 acres including many houses.

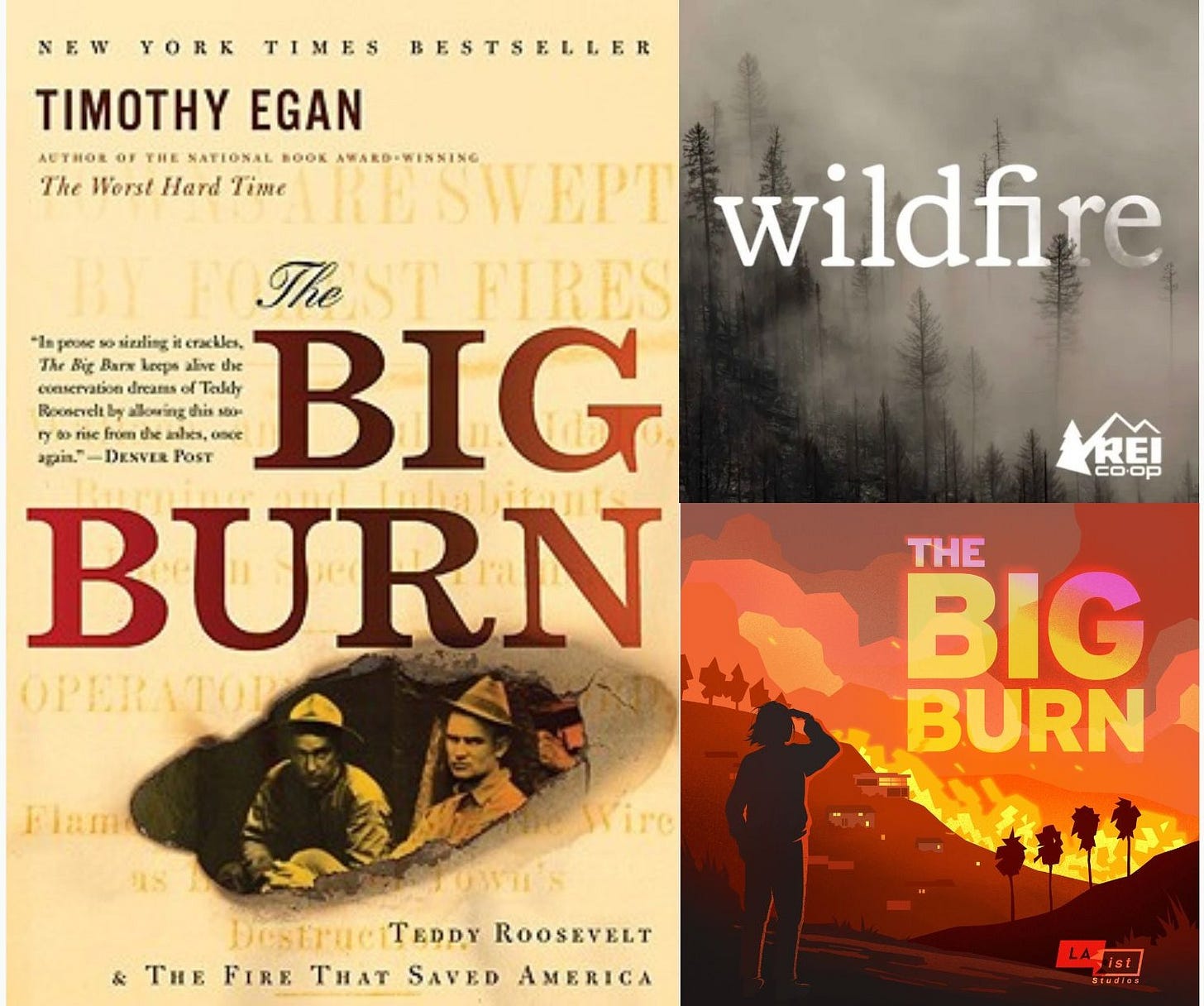

It was clear something had shifted. That, of course, is climate change. I don’t need to tell you that. But there are so many other factors that have made fires so much worse over the years. That’s where my fascination with fires come in. Since the Eagle Creek fire in 2017, there have been a couple of resources I’ve gone back to multiple times: Wildfire an REI podcast where the first season is dedicated to learning about Oregon’s Eagle Creek fire (thanks to the hosts being from here) and how we got into this mess in the first place and The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire That Saved America, Timothy Egan’s book about the massive wildfire that engulfed the forests of essentially the entire Idaho panhandle and part of Western Montana in 1910. The Big Burn is a vivid description not only of the fire itself, but also shows how it contributed to our modern-day fire policies of today.

It’s in this deep dive into the history of fire policy in the U.S. that I learned what Indigenous peoples in the U.S. knew all along: fires are out of control in the U.S. because of colonialism and capitalism made even worse by climate change. The Three C’s of fire I’m calling it.

For millennia, Indigenous peoples managed the landscape with fire that created healthy landscapes that benefit ecosystems and kept the fires that did happen less destructive. Through cultural burning—which involves managed prescribed burns—Native communities helped ensure there wasn’t excessive fuel (brush and debris) on the forest floor that would exacerbate a fire, makes room for new and healthy plant life, and kills off invasive insects that harm the trees. These cultural burning practices have formed the landscape here for millennia.

And then came the European colonizers stealing Indigenous peoples off their cultural land, killing wildlife on which Native communities depended, and attempting to erase Indigenous culture altogether. When it comes to land management, this essentially created a culture that assumed that Indigenous knowledge was inferior to the “modern” ways of the Europeans. This concept still holds within modern-day scientific practices and a cultural assumption that capitalistic interests was superior to deep knowledge rooted in understanding the land and natural landscape.

All of this created the circumstances for the 1910 megafire that burned 3 million acres across Eastern Washington, Northern Idaho, and Western Montana (called “the great burn,” “the Big Blowup” or what Timothy Egan called “The Big Burn”). The “letting the wild spaces go” approach of the Federal Government paired with the capitalistic interests of silver mining and logging that created a swift increase of populations in towns and communities along that corridor that made way for such a destructive fire.

It was that fire that led to the fire management policy we’re familiar with today: complete fire suppression. And for the last hundred or so years, that has how the Forest Service has worked—put out every fire that lights up and not allowing any prescribed burning. This approach became the end-all-be-all of U.S. fire management not because it was proven better but really because of fear.

That leads us to today, an era where in just a couple days tens of thousands of people have been displaced from their homes in one of the most populated counties in the country. The fire most definitely was exacerbated by climate change. But if the forests and landscapes around where the fires started had been managed in the method of prescribed burns and other fire mitigating land management efforts, it would not have been as extreme.

There have been changes in fire management in recent years where government entities are allowing for and, in some cases, even engaging in prescribed burns in partnership with Indigenous communities. But there are so many barriers to making that policy as extensive as it should be to create fire resilient landscapes better equipped to handle the fires made more inevitable by climate change.

What frankly needs to happen is to give more free rein to Indigenous communities who have preserved the ancestral knowledge of land management, which includes prescribed fire. Yet that is going to take a lot to get government entities to give over control despite not having the proper knowledge and even instincts on fire management. It requires a full paradigm shift in our relationship with fire. It would go from that fear-based all-fire-is-bad perspective to a we-need-fire-to-prevent-fire mindset (and at best an approach that learns to not just fear fire, but to respect and understand it better). But fear always gets us.

I hope the lessons we are learning from majorly destructive fires might change things. But we haven’t seen huge movement after other destructive fires. I think what it takes is us to reshape our relationships with fire to push our lawmakers to recognize that maybe our colonial-capitalist way of looking at things is, well, wrong.

If you’re interested in learning more about fire and fire management, the podcast and book I mentioned before are great resources (the Wildfire podcast and The Big Burn by Timothy Egan). I’ve also started listening to The Big Burn Podcast: How to Survive the Age of Wildfires produced by LAist studios. Both podcasts go into detail about what I’ve written about here and Egan’s book does an incredible job telling the story of how the modern-day Forest Service was created. I’ll admit that they are all produced or written by White men. Good companions to these that give context around Indigenous history and culture in North America are Robin Wall-Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass and Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous People’s History of the United States.

If you haven't yet read Fire Weather by John Vaillant I highly recommend!