The Dance of Climate Change Convos with Kids

And other challenges of raising a climate-conscious kid

Thanks to an orca exhibit at OMSI, Portland’s amazing science museum, my son and I have been talking more about climate change and healthy oceans. The topic comes up from time to time of course. It is something I think about every damn day, multiple times a day. So how couldn’t it?

But there’s a parental holding back that happens with me sometimes, perhaps because I’ve been in situations with Finch where I’ve said way too much about complicated topics–e.g., sex, bodies, race–that the conversation turns into overly emotional reactions (usually because my explanation was bad) or complete disinterest (usually because I drone on for too long).

Angela Garbes wrote about this in her book, Essential Labor and I related so much to her description of talking to her young daughters about sex where she says,

“At the dinner table, when questions get asked, one of my biggest challenges is keeping my explanations of things to under thirty seconds, when a child’s attention span fizzles out and I’m left talking about empire or the social safety net while both girls have moved on to biting apple slices into the shape of a boat or a moon or a butt.”

This happens to me so often with Finch that it made me wonder if, when things did get complex and he wanted to talk through them, would he actually want to talk with me about them. So, as of late, I’ve let him lead on the hard things. While that’s not necessarily going to work in all situations, it does help to get him to ask the questions and I can just take it from there.

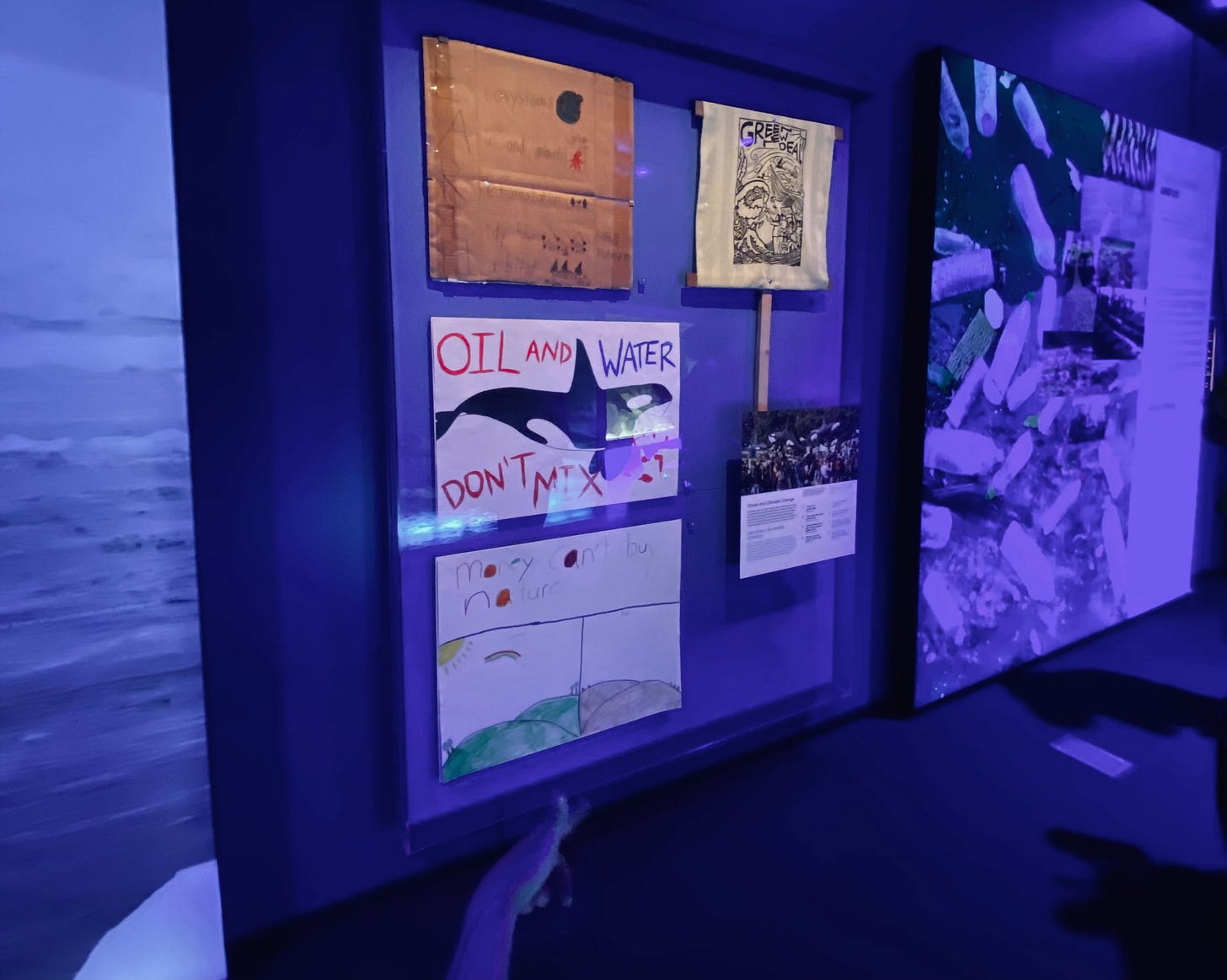

And so, after the Orcas: Our Shared Future exhibit where he was not only presented with the majesty and beauty of the orca and the cultural significance of orcas specifically to the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest (my favorite part), he was also confronted with their endangerment by way of excessive plastic in the ocean and oceanic noise pollution caused by huge boats. The concluding displays showed protest art about saving the oceans (which, as an art-loving kid, he wanted to get in on the action and make his own protest sign asap). This enthusiasm allowed me to explain in 6-year-old terms why and how the plastic garbage he saw in the display of netting and plastics removed from the ocean actually made its way there in the first place. Then on the way home, he began asking questions: “But how does all the garbage get into the ocean?” “What happens to the plastic when it gets there?” “Are the orcas and other sea creatures going to be okay?”

I was tempted to just go into the whole root of the problem, namely colonialism and capitalism. Then I took a deep breath. And thought of Angela Garbes again. She writes:

“I would rather err on the side of too much information, which is all I ever want, than not enough. But it’s a process, learning to hold back, dropping one or two important bits of knowledge, letting that stew in their little brains.”

And so I answered his questions simply. Sometimes he’d stop to think about what we spoke about and stare out at the cars alongside us in traffic. We eventually got to the topic of climate change and the planet warming (a connection he made from a display at the polar bear exhibit at the zoo, in fact). And he asks: “are all these gas cars bad?” I’m not exactly sure what I said, but I did want him to know it’s not always the individual choices that people make–as most people can’t have an electric car–but the companies that sell the oil that make the gas and that still we can do our best to make choices like not buy new plastic toys and such. He concluded our conversation with “Why can’t climate change stop now?!” “I don’t know, buddy, I know that’s why we’re doing all we can to make change by protesting and asking politicians to take action,” I responded.

And then he moved onto some other topic. Probably dragons. It’s usually dragons. But I was moved by our conversation. Moved because I was proud to see he was making the connections, but also moved to sadness because he has to realize the extent of the problem we’ve created for his generation. Of course, the scale of the devastation isn’t yet clear to him, but it will be. And that just sucks. It sucks that he has to have that realization and that we’ve messed up the future for all kids so much.

Meanwhile I’m still learning how to best have these conversations effectively. Similar to how White kids like myself were raised being taught color-blindness and weren’t given the tools to talk openly, frankly, and calmly about race, we privileged folks weren’t given the tools to navigate these conversations about climate change and environmental degradation. Like everything in the climate justice world, the privileged (read: me) are usually the last to wake up to the horrors thanks to our shield of economic stability. But they are ours to deal with nonetheless and we must develop those tools, particularly around climate justice.

But as I’ve noted, having these conversations while also developing those tools is not easy and it takes practice. I’ve found that broaching the topic out of the blue doesn’t tend to go over as well. Rather, I’ve been seeking out ways to immerse my kid in the topic. In fact, that’s what inspired a summer blog post I wrote for a climate justice organization I work with, Families for Climate, to give parents a bunch of resources to engage their kids in nature and climate education. And that’s exactly why we went to the orca exhibit. And the result was exactly as I hoped: a discussion about climate change.

I don’t expect every conversation to go as well as the post-orca car chat. I’ll take the wins where I get them. Sometimes I’m just so overwhelmed by the magnitude of the crisis that I can’t get anything coherent out. But that seems to be what parenting is all about anyway. You win some, you lose some, you move on and you try again. But the point is to continue to be that person who raises these complex questions. I also write all this knowing that not all kids take to these conversations as matter-of-factly as my own kid. In fact, Finch’s best friend (and my goddaughter) internalizes disaster scenarios deeply and her parents have to be very mindful about the way they communicate these things. (Although, I’ll say this, this sweet goddaughter of mine is going to be someone you want in the apocalypse because she is going to be as prepared as anyone).

As such, seeking out resources is always my go-to to help build these tools. This NPR Life Kit episode on talking to your kids about climate change is super helpful. Courtney Martin from The Examined Family recently interviewed the journalist from that very episode, Anya Kamenetz, and it is really great. And the other thing that I think is really important is working through my own climate grief on my own and really trying not to put it onto my kid in toxic ways. It’s that old “oxygen mask” metaphor we often talk about as parents–take care of yourself so you can be of more use to them. For that, Britt Wray’s Generation Dread was such an important read for me, and I’ve heard excellent things about the Good Grief Network. And frankly, this whole project is a part of me dealing with my own climate grief which has been essential for creating space to take care of myself while taking action as well as raising a climate-conscious kid.

But as everything is with parents, nothing is easy, yet we must persist.

Now I’m curious to hear from you all. How you’re talking to your kids about climate change. What has worked for you? What conversations have gone well or poorly?