Thanks to going offline during Spring Break with the kid, I’m treating you to yet another encore post. This feels pretty appropriate as a follow-up to my podcast interview with Brekke Wagoner from Sustainable Prepping last week. It’s something we talked about in the episode (which you can listen to here) and something that’s really great to ponder as we head into the 10 Weeks to Preparedness Series she and I have “prepped” for you (see what I did there?!)

With that, I present to you this encore post which was originally published on March 7, 2023. As of this writing, Spring has officially sprung over here in Portland and with the 50-60-degree weather, it’s hard to think about any winter storm. So, let me first put you into the scene of that moment of the original publication date approx. 13 months ago.

A couple weeks before I posted this story, we experienced a very large snowstorm. And while the forecasters were predicting it, the city was not prepared for the fast snow accumulation—businesses didn’t close soon enough, schools stayed open for the regular school day, and because of that many people were stranded on freeways and roadways (I wrote a tad bit about that here). And so, that is what had been on my mind for a couple weeks as I wrote this post. With that, enjoy!

I’ve been reflecting more on the “surprise” snowstorm in Portland a couple weeks ago, so I’m going to stick with it again this week because I think the subsequent fiasco poses some important emergency preparedness lessons, both for individuals and communities writ large. These lessons are about the responsibility of preparedness and what that means for those of us who have the time, the energy, and the money to do so.

During late February’s snowstorm, there were, indeed, many factors out of our control that caused the crapstorm of hours-long bumper-to-bumper traffic and abandoned vehicles on freeways. Those factors included a lack of preparedness by transit authorities and terrible communication on their part. As this Oregonian editorial from last weekend notes, while the snow wasn’t predicted to be as monumental as it was, there was still snow in the forecast. The urgency and the communication didn’t reflect as such and therefore, business progressed more or less as usual around the region until it was too late. Companies weren’t urging their employees to leave soon enough and there weren’t appropriate alerts.

Besides this lack of official alerts, it also seemed like decision-makers at offices around the region weren’t using common sense to keep their employees safe. While forecasters continued to maintain that the snow wouldn’t stick, you could just look outside an hour after the snow started and see that it was most definitely sticking. Yet people who had the power to send their employees home, such as my friends’ boss at her downtown office didn’t want to send people home until the entire company had made it official. It was almost the end of the day by the time that happened and many of those folks got caught in the parking lot on the freeways.

This inflexibility feels so rooted in that capitalistic adherence to the workday slog. And much of that is ingrained in company and institution policies that have certain rules about when employees can and should be sent home and what kind of leave they should take, which honestly seems like such a messed up way of viewing policies when people’s safety and security is at risk. It was clearly becoming less and less safe to be out. Employees don’t always feel comfortable just making the call on their own lest they get punished, so they’re beholden to their bosses’ decisions. And bosses are making decisions based on company policies that might feel unclear in these situations. The regional powers-that-be definitely receive some blame, but so do all the individuals who can make a decision that can, at the very least, help relieve the burden on their employees.

The consequences of poor decisions didn’t just affect employees. And those were numerous: people getting stuck in hours of traffic in cold, wet weather, some having to abandon their cars altogether. The consequences also likely made it harder for people who needed help to get it. Emergency vehicles can’t very well make it through a parking lot of freeway traffic to efficiently get to people in true emergencies. Snow clean-up efforts are likewise made more difficult. As such, making key decisions based on common sense–like closing an office early when the snow is clearly beginning to accumulate–can relieve the impact on transportation that much more.

On the individual level, there’s also a responsibility for preparedness among the privileged. Gathering the things you need in a disaster and being able to hunker down in your home on your own is a privilege. Same as creating emergency preparedness plans. It takes time, effort, and money to do so. It’s not something that every person has the mental space, the physical space, or the disposable income to focus on. Yet, folks like us do have the time and money to focus on this. As such, it is our responsibility to do what we can to keep ourselves safe so that, in the case of a disaster, we aren’t calling on emergency services. That we aren’t taking up scarce, necessary disaster resources and those can be concentrated on folks who need it. In the case of the snowstorm, houseless people come to mind.

This reminds me of a conversation I had with Regina Ingabire, the Community Resilience Outreach Manager for the Portland Bureau of Emergency Management (PBEM) as I was researching a story I wrote for CityLab a few years ago. The story was about a neighborhood in Northeast Portland, Alameda, where the residents had the privilege to prepare. This group had done a great deal of emergency planning as a community. “White, middle-class people have time, have money,” Ingabire said talking about the Alameda community specifically. “I imagine they prepare for disasters, have water, have food, extra cash. They have resources and they’re educated [on the potential for disasters]. If we have many people who are able and can do something on their own, that’s excellent. That means when things go down, the resources will go to the people who have less or who don’t have the opportunity, or don’t know what to do.”

Laura Hall, the PBEM’s Regional Disaster Preparedness Organization (RDPO) communications coordinator and a friend from my old neighborhood sees this as a personal ethical decision. “It’s my ethical obligation to not take up space [in shelters or hospitals that might be inundated in a disaster] unless I have a compelling medical reason,” she said. “Generally speaking, the less emergency responders and governments responders have to think about the people who are calling demanding things [e.g., restoring power in affluent neighborhoods], allows them to relieve vulnerable populations and move forward with recovery.”

“The snowstorm was an excellent example of why families need to have an emergency plan,” Laura wrote to me in an email this week as I told her about this story. “So many parents tried to rush across town and got stuck. Educators then had to remain at school with kids, and in some cases had to choose between students and their own families.” This shows that being prepared with a plan is our responsibility as well.

This sentiment was echoed by pretty much every person I interviewed for that CityLab story and it stuck with me. It underscored how preparedness is, in effect, a justice issue. It is a call for a sense of social responsibility, a responsibility to be mindful of our toll on an entire system, especially in an emergency. It is on us to care for ourselves because we have the resources and means to do so in an emergency and let the responders tend to the most vulnerable populations. Emergency preparedness on a personal level is part of caring for and thinking about our own role in the community as a whole.

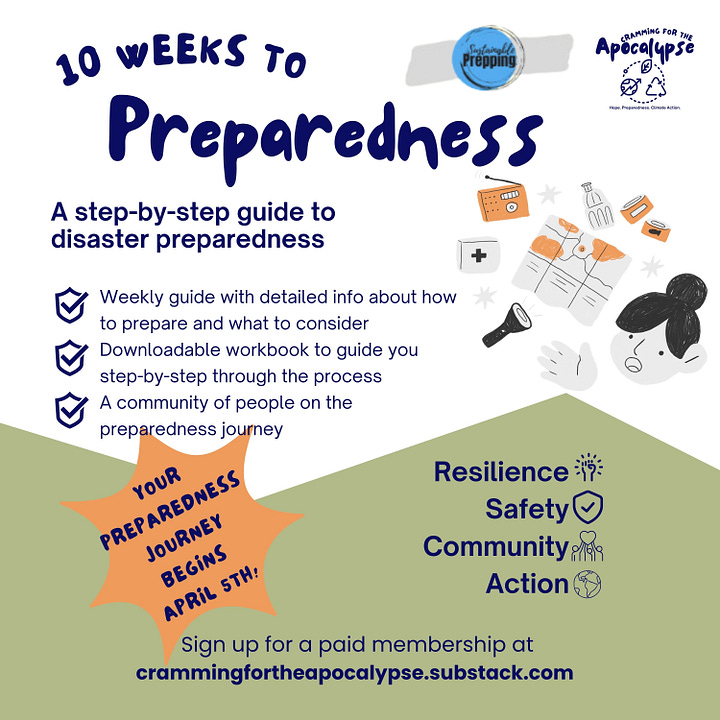

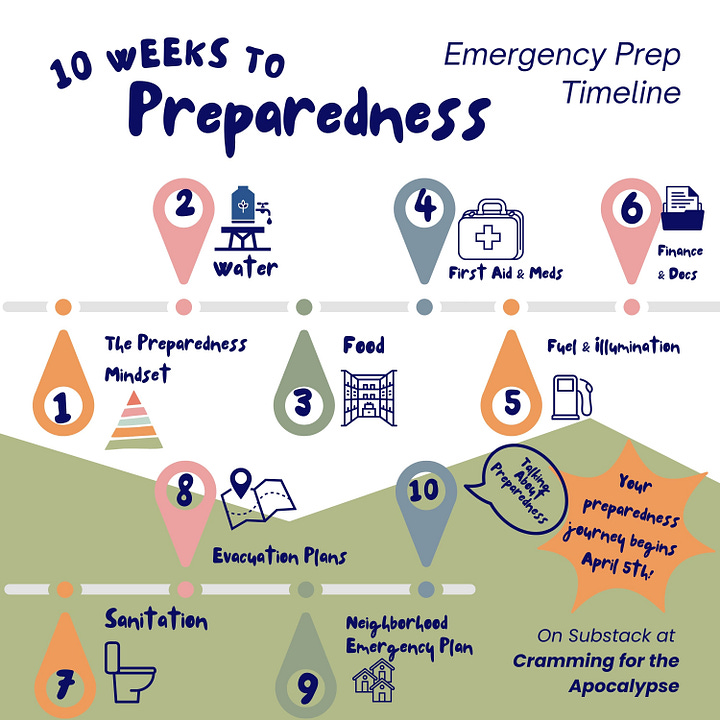

Now, read on in your best, infomercial voice in your head: Are you thinking about preparedness after this post? Are you worried that you’re not prepared? Well, you’re in luck, we can help you get prepared with 10 Weeks of Preparedness. Check out what you’ll be doing here and make signed up for a paid subscription to be treated to all 10 weeks of workbooks and guides.