Disaster Displacement, Environmental Justice, and Hope

A Somewhat Rambling Reflection on Jake Bittle’s “The Great Displacement”

In the wake of <name any disaster>, especially the kind where the destruction is predicted and inevitable (e.g., Gulf Coast cities and islands ransacked by hurricanes every season), there will always be a commentator or person-on-the-street-with-a-lot-of-opinions who will say “well, why didn’t they just move?” The logic is, they knew this was coming, they knew where they live is vulnerable to rising sea waters, they knew all of this. So why didn’t they just evacuate or even move altogether?

Most of us who have been thinking about, reading about, and concerned about climate justice know it’s not that simple. This victim-blaming approach is yet another way to put the effects of climate change on regular people rather than for those who are actually causing it (read: the fossil fuel industry and their supporters including our very own governments). And in this case, they’re putting that burden on the most vulnerable populations. Because in truth, the people who have the money, the time, the energy, and the privilege to do so, will leave. They will evacuate when a storm is coming because they have the resources to do so. They will maybe even leave permanently when the tides of climate change get too high to ignore. But those who don’t have the money or the resources have no choice but to stay. And besides, leaving one’s home is wrought with a lot of other cultural and emotional implications that aren’t as easy to place.

Oftentimes the victim blamers are onlookers from supposedly safe places watching these disasters on the news. Despite there being an increasing number of these disasters worldwide, this victim blaming approach–or even the approach of “oh, those poor people, I’d hate to be one of them”–implies distance. Those people are dealing with this. I will never be those people.

But in the face of climate change, we will eventually be those people. Our level of privilege might dictate how soon it will come for us, but our futures are wrapped up together and the signs of that potential future have been occurring for decades, but because it often affects the most vulnerable and under-resourced communities, we don’t hear about it as urgently or it might be easy to pass off as their problem and not ours.

Writer and journalist, Jake Bittle, is helping to change that. In his book The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration, he shows through detailed accounts of thriving and connected communities how people are already being displaced by climate change. What we see is that these particular communities were most at-risk for displacement because of a multitude of past decisions and practices put in place including racism, segregation, poor city and regional planning, and a huge lack of foresight thanks to the steady and unimpeded forward momentum of American industry. But the chickens are coming home to roost and we can’t ignore it any longer.

“For a long time climate change was something to be discussed in abstract terms, something that existed in future tense,” Bittle writes. “That is no longer the case.” The Great Displacement shows through the personal stories elicited from hundreds of interviews that we are already experiencing the devastating, societal-shifting effects of climate change. And of course, as our economic and social system is designed, it’s impacting those with the least power and the least money first and most.

The Great Displacement shows that many of the people in these communities had no choice but to live in these areas as well as the incredible burden–financially, logistically, and emotionally–to leave one’s home. And the way our economic system and our lack of social support built into local, regional, and national governmental structures, there is very little assistance given to these community members.

One example Bittle shows is the environmental justice impact on Black Americans displaced over the period of decades from the historically Black neighborhood of Lincoln City in Kingston, North Carolina. From its beginning, Lincoln City was a place of refuge for Black Americans recently emancipated from enslavement after the Civil War ended. Like so many Black communities, it was built on land White folks didn’t want. Yet the founder, Lincoln Barnett bought the swampy land and there emerged a thriving, connected community. The community has continuously experienced flooding over the years and had become accustomed to it. But with climate change, the frequency and severity of the flooding began to make the community unlivable.

There were a series of proposals to residents in Lincoln City by the City of Kingston and most recently a program to buy out people from their property to incentivize them to leave. But it’s never as straightforward as providing the capital to leave. There’s still so much that is lost from displacement. When Bittle spoke with Danny de Vries, a geographer who wrote his dissertation on Lincoln City, de Vries said this: “I’m curious what your goal is here. If you’re trying to say this was a success story, and this is how things can be done to relocate an entire community, then I’m not so sure. From a governmental perspective of trying to get people out, it was a success; but from a human and cultural standpoint, it was a tragedy.”

His words echo those of the Black communities who were dislocated and destroyed because of highway expansion during the urban renewal era that plowed through thriving communities of color to build freeways. While the displacement of Lincoln City residents was because of the inevitable creep of nature, relocation for any means is fraught.

Of course, disaster comes in many forms and the post-disaster scenarios might play out differently. Bittle uses each chapter to show the different ways disaster and displacement might play out and how they affect people in those communities.

I thought of The Great Displacement during a particular passage of another book I’m currently reading, The Light Pirate by Lily Brooks-Dalton. [A disclaimer: I am currently in the middle of the book, so this is all just pure observation from a reader-in-the-middle-of-reading–also a reader listening to the book, so the formatting of the passages below are probably not correct :)] It’s a climate fiction book that takes place in the not-so-distant-but-distant-enough future in the fictional town of Rudder, Florida, where Florida is literally washing away. It’s centered around a child born amidst a devastating hurricane and her family who are working class folks, the men in the family being linemen helping to get the lights back on after the constant barrage of hurricanes.

In one scene, one of the characters is catching up with his high school sweetheart, a wealthy enough person who is back from grad school one last time to clear out her parents’ house after they’ve moved to Denver. His realizations in the moment of their reunion show the very emotional toll the thought of leaving a place can be in one’s mind, no matter how doomed it is:

“The idea of leaving has taken root in him. But to demean this place in the process, to judge it as unworthy of himself–of anyone, really–is to belittle its land, its inhabitants, its struggle, its history. He doesn’t need Rudder to be not good enough in order to go somewhere else.

‘I like the program, mostly,’ she goes on telling him about Chicago, about her summer travels in Europe, about the people from Rudder she’s kept in touch with, and the people she’s lost track of. He listens, is politely attentive, but none of this matters. Not really.

She’s telling him stories about a world that doesn’t know it’s ending. This world is worried, of course, about climbing temperatures and vengeful wildfires and rising tides.

‘The Headlines are absolutely terrible,’ she says. ‘Incessant, exhausting, but they're just that. Headlines.’

Things that happen to other people, elsewhere. The Middle East, Indonesia, Northern California, The Bahamas. ‘Those poor people.’ Southern Florida and the Keys, Louisiana, Puerto Rico. ‘Those poor people.’ The safe zones have shrunk, will go on shrinking. But the people still firmly attached to the idea that there will continue to be such lines between ‘safe’ and ‘not safe,’ between ‘us' and ‘those poor people’ are determined to go on as they always have.

And here is one of them.”

This book takes place in a future that is moving towards dystopia. But these earlier passages are close enough to our reality to know that this depiction of “us” and “those poor people” will continue to exist no matter how bad it gets. What creates this is a gaslighting from industry, from government actors who could take powerful action now yet just won’t, from our capitalist culture, that we will be okay in the end.

The Great Displacement shows that is already not true. Many people are currently not okay. Many people have been displaced already because of the climate crisis.

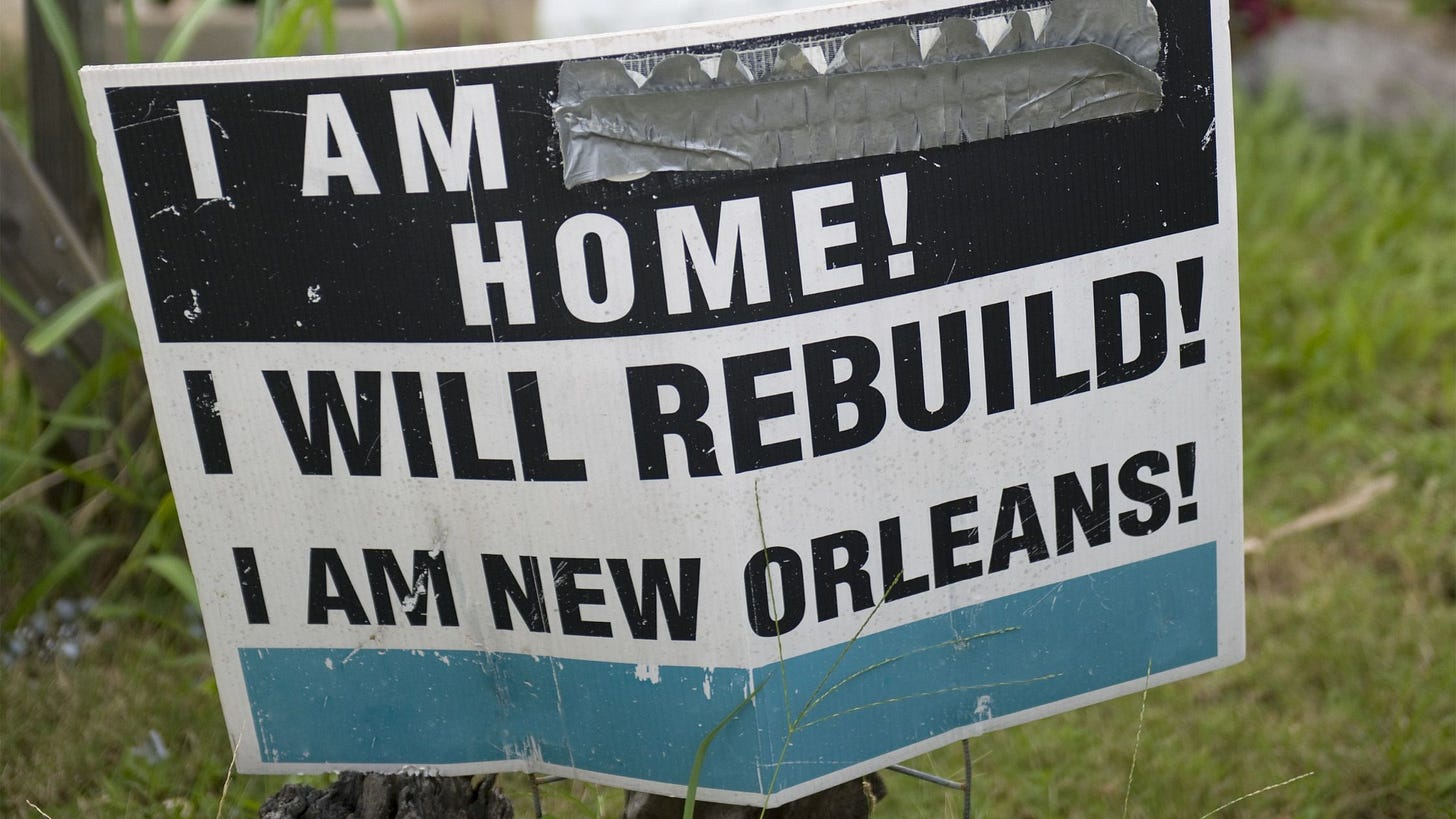

It’s a hard book to take in because in the end, the climate crisis has progressed long enough that there will be places that cannot be saved. But it is not all hopelessness.

“On the other side of this loss, there is an opportunity–an opportunity to rethink this idea of home, or reform it, or create it anew,” he writes. “Tackling climate change in the short term will mean ending the hegemony of oil and gas, decarbonizing the economy, and retrofitting vulnerable communities for a dangerous new world. In the long term, it will require building a political system that can support people through the climate shocks that are already inevitable.”

There is hope. We must start with seeing and acknowledging what’s happening and learn from our mistakes and create more resilience in order to manifest this hope. With hope and willingness to make change, this is not where it ends, perhaps it could be a new beginning.